An academic administrator voices a common but misguided concern: how did our research university wind up with so many non-research faculty who teach basic courses like general education (GE) writing? Originally, they were supposed to fill in part-time when regular faculty went on sabbatical. Now they seem a permanent fixture.

How indeed?

Perhaps polemically, some fantasise about research faculty teaching everything from GE writing to Spanish sections to biology labs. But this fantasy is not just economically impractical; it misses the point about good teaching. A basic contradiction at the heart of the modern research university devalues the very wisdom that allows it to function practically in the first place.

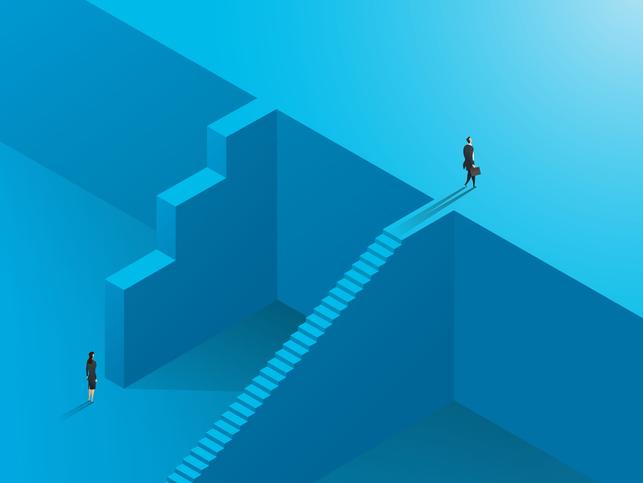

If non-research faculty such as adjuncts and lecturers disappeared, an entire domain of knowledge crucial for instruction would disappear with them: instructional know-how. This is not the ability to teach per se, but rather a specific kind of practical knowledge developed most readily in a teaching community where collective wisdom – not published research – serves as the knowledge base. In the current university system, know-how typically does not count for review and promotion at any level, whereas information production (know-that) counts for almost everything. This is true as long as the information is generated by those who are employed as researchers. A lecturer colleague of mine was told, for example, that his many relevant academic books showed up as a hobby, like gardening, when it came to review.

- How to get promoted from an adjunct to a permanent position

- It’s time to fully support promotions on the education pathway

- We must dismantle the invisible career barriers in HE

It was Oxford philosopher Gilbert Ryle who made the knowing-how and knowing-that dichotomy famous. In his 1945 presidential address to the Aristotelian Society, he argued that a long history of philosophy going back to Plato distinguishes intelligence as a special faculty exercised through acts of thinking. Practical activities, by contrast, only rise to the level of intelligence when accompanied by thought, which according to Plato is superadded. In opposition to this doctrine, Ryle shows that “intelligence is directly exercised…in some practical performances”, and he offers a demonstration that knowledge-how is a concept logically prior to the concept of knowledge-that.

Ryle’s examples tend towards the personal: “A good experimentalist exercises his skill not in reciting maxims of technology but in making experiments. It is a ruinous but popular mistake to suppose that intelligence operates only the production and manipulation of proposition, i.e., that only in ratiocinating are we rational.”

Adopting Ryle’s distinction, I emphasise instead the irreducibly social quality of know-how. It can be embodied in collective wisdom exceeding the capacity of any individual; indeed Ryle himself might have acknowledged that the skills of a good experimentalist can't materialise, or will amount to precisely nothing, without things such as laboratories and the largely communal apparatus that makes a laboratory what it is. The basic distinction is well understood in scholarly circles. What is poorly understood is how and why knowledge-that ultimately prevailed in the research university despite a debilitating contradiction, and at what expense to everyone involved.

The contradiction can be expressed through three anxieties:

Anxiety 1: Know-how is guildlike

Know-how remains reminiscent of our pre-Enlightenment past, when the darkness of local interests prevailed.

Instead of provincial knowledge, knowledge in the modern university system, articulated in Europe at the turn of the 18th century, would be universal, which also meant communicable across regional and national boundaries, languages and modalities. The embodied know-how of a master might have its local virtues, but systematic and universal knowledge would have to function on other terms that could be communicated in discrete units – a scholar’s every perception, every thought – transferable from one local context to the next by way of shared language. What we now consider “knowing-that” would appear most readily in the emerging learned journals, more popular publications, society meetings and letter exchanges that ultimately produce a dynamic world of scientific facts articulable in propositions or in symbols that can be universally recognised.

Anxiety 2: Know-how is inherently suspect

Know-how is associated with the wrong kind of instruction, which detracts from the primary mission of the research university.

The postwar triumph of the modern research university tracks directly and overwhelmingly to federal funding for natural science research and development, the efficacy of which is reinforced most consequentially through science publication indexes that authorise knowledge in an important but very particular way outlined above. Teaching becomes secondary.

And so to wind down…

Anxiety 3: The ‘service’ trap

Since federal grant funding and peer-reviewed publication by research faculty is the coin of the realm, anything else we do at the research university is at best service, and at worst counterproductive with respect to institutional prestige. When domains of know-how, such as learning communities, are recognised, they are typically oriented towards student research and study, not civic and community engagement, not professional development, and not any form of practical know-how that might in fact be a precondition for original research, just as Ryle indicates by way of his experimentalist.

So, what to do?

Remember what Ryle wrote about the good experimentalist who exercises their skill not in reciting maxims but rather in making experiments. Similarly, we who are familiar with large writing programmes, for instance, can say that the good writing instructor exercises their skill in writing instruction, which doesn’t mean imparting knowledge-that but rather materialising know-how in its richest sense. This includes the practical and collective wisdom that can only be produced locally by way of instructor-generated assignment databases, staff meetings, curricular exchanges, corridor conversations and the accrued experience that makes our instructors deeply qualified.

Finally, an achievable short-term goal. This short story I’ve told militates against instruction that is part-time, adjunct, temporary, remote. Know-how in our world can’t readily accrue when individuals are relatively disconnected from both each other and the institution where they work. The value of know-how in the research university and beyond is immediately enhanced when instructors are full-time, eligible for tenure and materially supported in their collective endeavour by way of, say, a universal course release for programmatic service and professional development.

At research universities, such an arrangement is now sometimes the case. Here I have outlined new reasons why such an arrangement should be the norm.

Daniel M. Gross is a professor of English, campus writing and communication coordinator and faculty director of the Center for Excellence in Writing & Communication at the University of California, Irvine.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

comment